Obst & Muse

Permanent exposition of Stano Filko in Central Slovak Gallery in Banská Bystrica. Hydrozoa, Part 6.

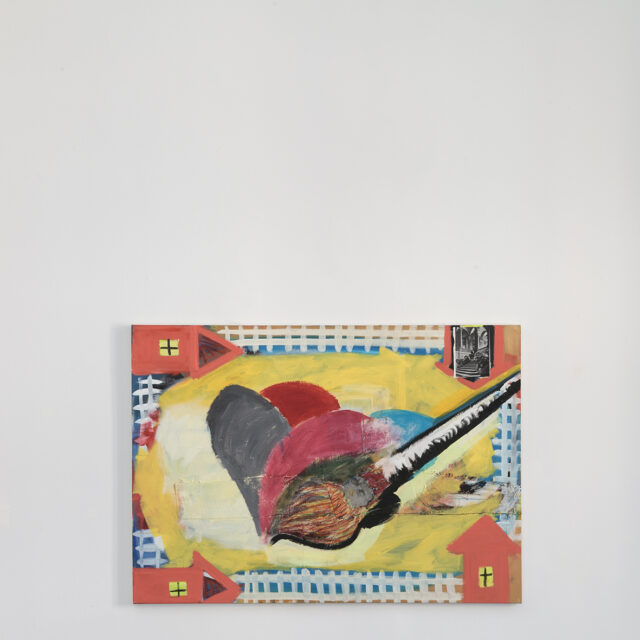

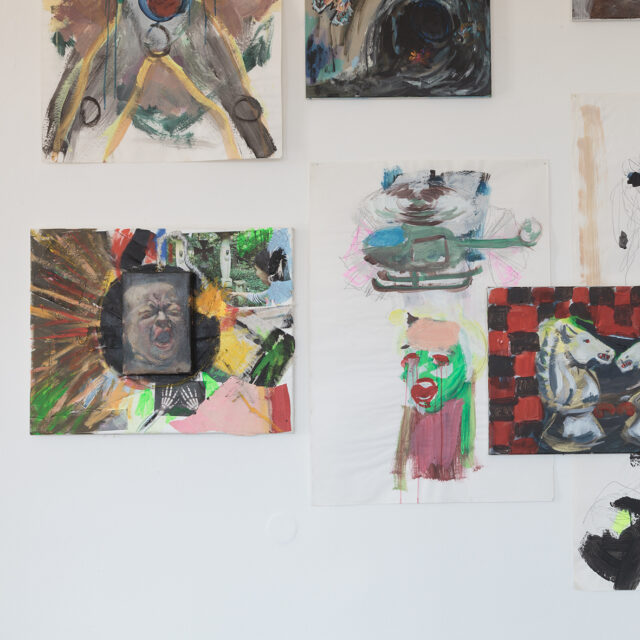

The intention of the Permanent exposition of Stano Filko at the Central Slovak Gallery in Banská Bystrica, Hydrozoa (est. 2017 after acquiring an extensive collection of Filko’s works of archival and project nature) is to create a specifically conceived long-term exhibit of the works of the neoavantgarde artist Stano Filko (1937 – 2015). The idea behind the project is to expand knowledge of Filko’s radical work through the engagement of contemporary artists who update his legacy in new ideological and relational frameworks. Part 6 of the series develops a connection to Filko’s neoexpressionist period from the time of his New York residency in the years 1982 – 1991. The historical neoexpressionist tradition brought a revival of figurative painting, which continues in contemporary postexpressionist painting. Authorial superfiction of the Martin Kippenberger’s bad painting similarly grows out of appropriated and collaged cultural imagery. Roman Bicek as Robert Rauschenberg (Skateboards, 1977) once did, designed a series of original skateboards (Atelier SAMA, 2022) or installed crooked hanging paintings (Atelier XIII, 2021) like Jean-Michel Basquiat (New York, New Wave, 1981), who similarly composed elements of street culture, including skateboarding. Filko and, in a more non-pathetic, sarcastic position, Bicek share these practices, though not in the sense of masterful style-making, but rather of creating an anti-style, discursive engagement with anarcho-street culture.

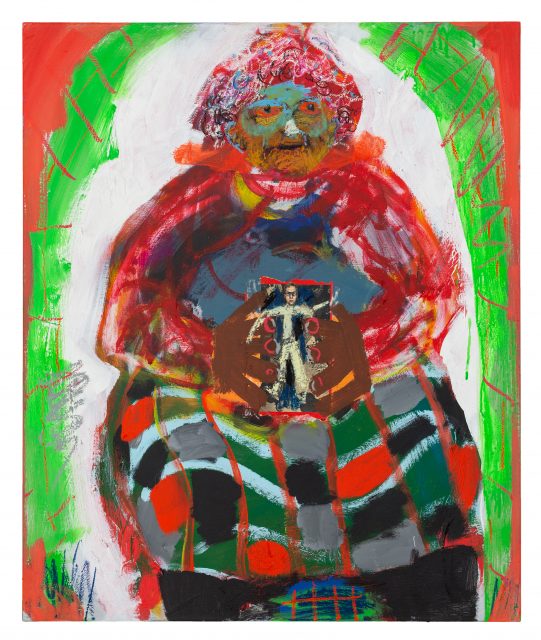

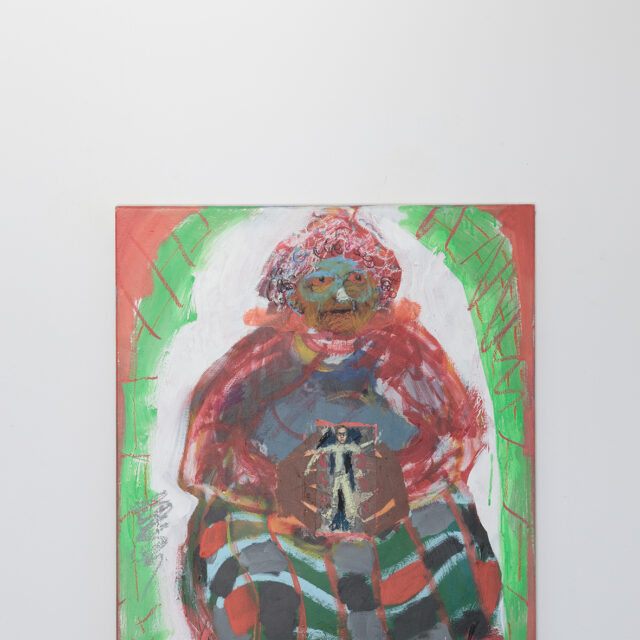

As part of the first neoexpressive wave, during his American period, Filko painted lettristic transcriptions (variations of his name or the acronym AIDS as an attribute of New York’s culture wars), which he installed in assemblage installations and linked to his iconic Altars from the 1960s. He further interpreted these in a Leviathan-like manner as the so-called dance macabre of the new crisis of civilization. From there he then conducted his contradictory dialogue of altruism with egoism, influenced by the Christian doctrine of the so-called virtues given from above. At that time, he also created animal frontal scenes of matrons without a closer identity or women, reduced in a graffiti-like manner to anatomical figures of wombs or vaginas, also in a version of the so-called vagina dentata. He also depicted figures of lecherous men, imagined by figures of the mythological Pan or indulgent baroque old men. Several of his series of enlargements of gaping mouths and teeth were revelations of dangerous-looking beings, potentially devouring or castrating, with pornographic features, but which Filko constructed patriarchally. They follow artistic tradition of the Gorgon Medusas as both bloodthirsty and accepting matrifocal mother goddesses, monstrous but at the same time burlesque, erotically self-exposed and girlish; women as they appear in the works of modernist artists, which were critically thematized by feminist culture. While in the 1990s Filko pushed the limits of his essentialist position towards the hermaphroditic figures of sci-fi Paleolithic Venuses, Bicek’s hybrid beings were already constructed by feminist optics.

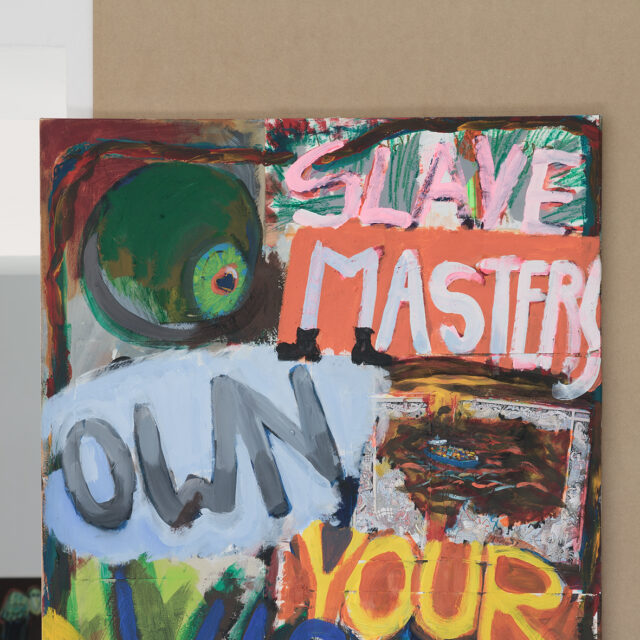

Bicek handles the critique of the system and the development that have shaped it with an awareness of the often-paradoxical perspectives that seem to be stuck once again on the topic of social identities of the new universalism instead of solving social inequalities in the current culture war between conservatism and liberalism. This is the case, for example, in the radicalizing online subculture of the incels (a neologism from the 1990s as an abbreviation for the self-definition of the so-called Involuntary Celibates Men) forming around misogynistic dogmas derived, for example, from biological determinism. The position of the incels is most often explained as a consequence of isolation or social anxiety, which is supported by the belief in selective social equality based on the denial of emancipatory gender politics. The community is ideologically mobilized especially against social constructionist opinions linked to feminism and interacts, for example, in the so-called manosphere of antifeminist websites. As a path of personal validation, it escalates into extreme right-wing or so-called alt-right expressions of hatred and violence against others, which is evidenced by several recent attacks on selected communities.

The subject of Bicek’s critical and humorously rhetorically framed investigation is thus the world of clashing dogmas, which, for example, in obscene sarcastic painting memes also talks about the spectrum of the increasingly mainstream community of incels, which in the cultural process of deconstruction of the patriarchal order of the last decades has been united by the motif of discrimination of masculinity, or otherwise of male superiority. The imagery of a world of non-dialogical conversations in which no common ground can be found anymore because they become nothing but a struggle for dominance, war zones of all that culture has cultivated, a Hobbesian war of all against all, absurdizes the ultra-conservative distortion of seeing identities as essentialistically fixed and opens up the understanding of (even traditionally male) identities constructed in the process of their performance. As the ongoing feminist revolution and in general the dynamics of the individual and the social have diversified the cultural field since the neoexpressive wave of the 1970s and 1980s, the culture wars have also changed their specific actors. And so, while ongoing change develops a more just relational ethics, it also reinforces more unjust perspectives of superiorities and normative collective identities constructed on the background of populist strategies. Using the example of gender wars or inequalities of postcolonialism, the exhibition follows the clashes of illiberal modernities with liberal ones. Since the future is scary; there is nothing more to desire, neotraditionalism without a vision turns its attention to the past, to the traditional, seemingly original, so-called natural. In reference to Filko’s new-ageist psychophilosophical system, the choreography of the exhibition also loosely follows the filmmaker and writer Alejandro Jodorowsky’s psychomagic concept of trauma-therapy, also anchored in surrealism. The latter targets deep-seated psychological injuries and family traumas. It is also close to Filko’s performative practice, in which he sought to avoid style-making and a unipolar interpretation of the world through constant self-actualizations. Bicek’s harshly mythopoetic, retroexpressive imaginary extends this notion into broader communal and cultural frameworks. Identitarian autofictions merging with culturally produced archetypal imagery can also be seen in the figurative painting tradition as symbolic acts of healing imagined inner demons. Since we cannot broadly agree on the nature or observation of permanent change, we remain stuck in unchanging hierarchies and reproductions of ourselves in reflections of others that we experience as real. The eternal transformation that has been the fascination of non-canonized avant-garde art in general is what the burgeoning industry of so-called new spirituality, whether in unregulated so-called psychotrashist or established transhistorical practice, seeks to encompass. The idea of connection to a kind of cosmic consciousness thus collides with the rise of neoliberalism, as it once did during the rise of neoexpressive painting and the conservative turn of the 1970s, when Thatcher – who had no less ambition than, say, Castro, famous for the quote that not even sex can stop a revolution – said that she didn’t want to change just material reality, but also the soul of the human being. From new-agism to self-help practices that cover a multitude of spiritual beliefs, in an age of transactional medicine, necessary personal healings and coveted self-developments, even the new spirituality necessarily becomes an individualistic self-expressive tool of symbolic transformative imagination, but one that, apart from the alchemizing of so-called well-being, has little aspiration for the necessary expansion of the political imagination as well.

Text Mira Keratová

Roman Bicek (born in 1981) is an artist and lecturer at the Department of Intermedia at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Bratislava. He graduated from prof. Ivan Csudai’s studio at the Department of Painting at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design, and previously studied at Wimbledon School of Art and Leyton Sixth Form College in London. He has exhibited individually and collectively in Slovakia and abroad. As part of a collective of artists, he led the HotDock Project Space gallery in Bratislava – Petržalka (2010 – 2022).

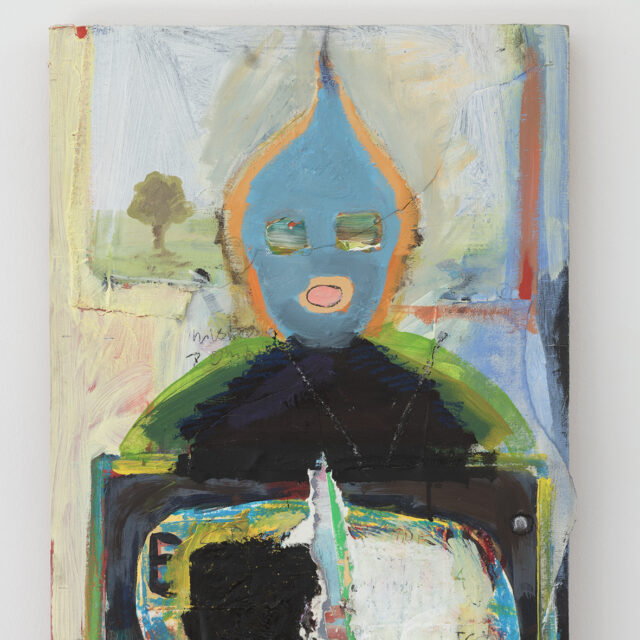

Artwork: Roman Bicek: Rote Volke, 2021. Acrylic, pastel, collage on canvas and paper, 90×75 cm

///////

Title of the exhibition: Obst & Muse. Permanent exposition of Stano Filko in Central Slovak Gallery in Banská Bystrica. Hydrozoa, Part 6.

Artist: Roman Bicek

Curator: Mira Keratová

Exhibition architecture: Matej Gavula

Venue: Central Slovak Gallery, Praetorium, Štefan Moyses Square 25, Banská Bystrica

Duration: September 16 – December 3, 2023

Opening: September 16, 2023, 5. p.m.

Supported using public funding by Slovak Arts Council.

The founder of the Central Slovak Gallery is the Banská Bystrica Self-Governing Region.